Last month was National Poetry Month and, due to the prompting of a fellow employee, I found myself contemplating similarities between the early stages of drafting processes for essay and poem writing. I feel that it’s necessary to inform you that I am a poet; however, I am also a supervisor/consultant for the Graduate Writing Studio at Fresno State. It is my daily duty to help students with their writing and I am often engaged in the necessary discussion of how to get writers started on a project, any project.

Sitting down to write a poem is a struggle. Most writers, of any genre, find themselves in this position and I speak to students on a daily basis regarding this dilemma. Often, I find myself boring our over-worked students with a brief anecdote intended to help them feel less alone—that I, too, have writing troubles. I make sure that they know that from the moment I sit down to write, I—like them—inevitably trip over several types of stumbling blocks: self-doubt, comparison (to my past work and other writers I admire), a vacancy of ideas, whether or not I should be folding laundry or washing dishes or taking out the trash instead, or I’m asking the big question: why is my writing important or necessary? These thoughts are problematic and should be avoided. This avoidance, though, is easier said than done.

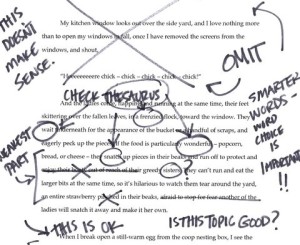

As writers, we are all faced with the initial problem of getting started with that first  draft. In Anne Lamott’s edifying essay Shitty First Drafts, she claims that “the first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later” (22). I wholeheartedly agree; but how do we get to that place of play or freedom? The answer is not magical; there is no easy way to turn on the stream-of-consciousness-Kerouac-switch in our brains. The answer comes in the form of rigor, hard work, an unrelenting schedule, and draft after draft after draft until we have something that can be let loose into the intimidating world of scholarly works.

draft. In Anne Lamott’s edifying essay Shitty First Drafts, she claims that “the first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later” (22). I wholeheartedly agree; but how do we get to that place of play or freedom? The answer is not magical; there is no easy way to turn on the stream-of-consciousness-Kerouac-switch in our brains. The answer comes in the form of rigor, hard work, an unrelenting schedule, and draft after draft after draft until we have something that can be let loose into the intimidating world of scholarly works.

As poet Richard Hugo so eloquently states in his essay The Triggering Town, “The hard work on the first poem is responsible for the sudden ease of the second. If you just sit around waiting for the easy ones, nothing will come” (17). Hugo is not only revealing a  disappointing truth about the illusion of inspiration, he is also letting us know that, if we spend our time waiting, nothing will get done. With that being said, a poet should begin writing whether or not there is something to write about. A student/essayist, similarly, should be taking notes while reading source material. These actions motivate the writer to begin thinking about the content of their first draft in a way that is almost subconscious. But, thinking about adding one’s poems to the world of the great poets or contemplating that jump into the bigger academic conversation can be intimidating.

disappointing truth about the illusion of inspiration, he is also letting us know that, if we spend our time waiting, nothing will get done. With that being said, a poet should begin writing whether or not there is something to write about. A student/essayist, similarly, should be taking notes while reading source material. These actions motivate the writer to begin thinking about the content of their first draft in a way that is almost subconscious. But, thinking about adding one’s poems to the world of the great poets or contemplating that jump into the bigger academic conversation can be intimidating.

Academia is scary. We read scholarly articles and studies and we may find ourselves shrinking away from that kind of writing. Perhaps we are thinking: “how in the world can I write this way?” This is a similar experience for the creative writer. A dedicated artist should always be engaged in the work of others, whether contemporary or classic. In addition, we poets are always thinking about the development of our individual voices. Students should also consider their own voice when composing an essay. Intellectual or unique language in one writer’s work will never be another writer’s way of speaking. Ben Lerner, author of The Hatred of Poetry, makes clear the problem of a poet aspiring to sound like another. He says, quite bluntly, “if poems are impenetrable, they are elitist” (77). This is important to keep in mind if one finds oneself attempting to emulate the apparent intellect of another author, no matter what we are writing. The truth is this: our own scholarly voice comes from our knowledge of our subject matter/material, along with the ability to construct a clear sentence, and nothing else. The statement “write what you know” has been a mantra for poets since it was first mentioned by Mark Twain. The same goes for  any writer of any genre. First know your stuff and then, as Hugo would say, “get to work” (17).

any writer of any genre. First know your stuff and then, as Hugo would say, “get to work” (17).

That first “shitty draft” will never write itself. Create a rigorous schedule and make it a necessity to be productive during the hours of the day when your brain is most active. For me, this is early in the morning. For others, it may be late at night, in the middle of the day, or at the horse races. Then be sure to give yourself a goal. My goal, for instance, is to create one finished poem a week. This means that two or three poems (or multiple drafts of the same poem) may need to be written in order for me to end up with an acceptable result after seven days. If your essay requires fourteen sources, perhaps you can attempt to write seven summaries a week for two weeks. It is also extremely important to offer yourself a reward for each weekly accomplishment. Remember to be strict with yourself. Be responsible for your goals and your rewards.

Finally, write about something that is of interest to you. Your subject matter needs to have relevance to you on some level. Richard Hugo knew that the “trigger,” or motivation, for a poem should be one that lights that flame of inspiration for the writer. So pick a subject that is meaningful: “Your triggering subjects are those that ignite your need for words” (15). There is nothing worse than a poet who writes about something that doesn’t interest them or that they know very little about. For instance, I may want to write a poem about the Great Depression, but if I have no experiences or have not taken the time to gather research to support or add to my knowledge of the subject, I will inevitably fail in my attempt. Similarly, a student who writes an essay about something to which they are not attached will truly dread the process of gathering research and will write a lackluster piece.

All writers, at any level, should remember that we are in this together. Writing is difficult for everyone. There is no romance in the act of writing poems, nor is there a need for intellectual prowess in academic writing. We learn, as students of any subject, that we are responsible for our own contributions. Putting in the hard work, maintaining rigorous practices, finding the courage to resist our own insecurities, and maintaining productivity despite our fears and busy lives, are ways we can learn to have confidence in ourselves as scholars and as participants in a conversation that will always seem bigger than us.

by Ronald Dzerigian

Works Cited:

Hugo, Richard. “The Triggering Town.” The Triggering Town, W. W. Norton & Company, 1979, pp. 15 – 17.

Lamott, Anne. “Shitty First Drafts.” Bird by Bird, Anchor Books/Doubleday, 1994, p. 22.

Lerner, Ben. The Hatred of Poetry. Farrar, Straus and Giroux, 2016, p. 77.

We all know the feeling of coming back to another semester of grad school. Intense lectures and seminars, long hours of studying and preparing for exams, meeting after meeting with professors and advisors, and of course hours upon hours of writing. Simply put, life as a graduate student can be extremely demanding and at times, very overwhelming. For the most part, no matter the program you may find yourself in, the truth is you will be required to do lots of writing and eventually write a thesis, dissertation, or project. As a second year graduate student, I would like to share several tips on how to start the semester off strong, successfully make it to finals week, and eventually graduation.

We all know the feeling of coming back to another semester of grad school. Intense lectures and seminars, long hours of studying and preparing for exams, meeting after meeting with professors and advisors, and of course hours upon hours of writing. Simply put, life as a graduate student can be extremely demanding and at times, very overwhelming. For the most part, no matter the program you may find yourself in, the truth is you will be required to do lots of writing and eventually write a thesis, dissertation, or project. As a second year graduate student, I would like to share several tips on how to start the semester off strong, successfully make it to finals week, and eventually graduation.

Giving yourself time to refresh is crucial to your success. It serves as a way to reward yourself for your hard work during the week, and motivate as well, by giving you something to look forward to.

Giving yourself time to refresh is crucial to your success. It serves as a way to reward yourself for your hard work during the week, and motivate as well, by giving you something to look forward to.

It is important to educate our students on how to identify plagiarism, how to avoid it, and how to cite correctly. In fact, our librarians at California State University Fresno’s Henry Madden Library, offer workshops on “Avoiding Plagiarism” and our Grammar for Grad Students Series has also included a session on plagiarism.

It is important to educate our students on how to identify plagiarism, how to avoid it, and how to cite correctly. In fact, our librarians at California State University Fresno’s Henry Madden Library, offer workshops on “Avoiding Plagiarism” and our Grammar for Grad Students Series has also included a session on plagiarism. the ideas embodied in the research and know how to cite appropriately. This requires much more than substituting a word here and there or re-ordering a sentence. If a student has taken the time to research and understand the topic, they will be able to communicate the issues embodied in the topic in their own words.

the ideas embodied in the research and know how to cite appropriately. This requires much more than substituting a word here and there or re-ordering a sentence. If a student has taken the time to research and understand the topic, they will be able to communicate the issues embodied in the topic in their own words.

searching their biological instincts to find a way to survive the experience. They also trust that, if they fail, they will be saved. Throw the student in, but be there to save them from drowning. Grammar, logical continuity, syntax, research, outlining, the drafting process, and other processes have been a part of every graduate student’s life at some point—this is their pool of water. They may not have the vocabulary to explain these things and they may not know how to explain the functions of language on the page—they may not know that they already know how to swim—but they have been exposed enough to paddle their way to safety.

searching their biological instincts to find a way to survive the experience. They also trust that, if they fail, they will be saved. Throw the student in, but be there to save them from drowning. Grammar, logical continuity, syntax, research, outlining, the drafting process, and other processes have been a part of every graduate student’s life at some point—this is their pool of water. They may not have the vocabulary to explain these things and they may not know how to explain the functions of language on the page—they may not know that they already know how to swim—but they have been exposed enough to paddle their way to safety. Students often get caught up in sounding scholarly. When encountering this, try to ask them, “How would you write this sentence?” Often, after they have let go of that Jiminy Cricket on their shoulder who is telling them that they need to write to a scholarly audience, they dismantle the facade and rewrite the sentence in their own authoritative voice. These students haven’t quite learned that they have already become the scholars and they definitely do not trust themselves. How do we show them how to trust themselves? We ask them to explain the subject in their own words. We should listen, ask, and then listen again. They have the tools and a constructivist approach would assume that they would find their way. A consultant should say “there is the pool,” throw them, in and be the “life jacket” in case the student flounders. Nine times out of 10, the student will find their way toward a clear, scholarly, voice that belongs to them.

Students often get caught up in sounding scholarly. When encountering this, try to ask them, “How would you write this sentence?” Often, after they have let go of that Jiminy Cricket on their shoulder who is telling them that they need to write to a scholarly audience, they dismantle the facade and rewrite the sentence in their own authoritative voice. These students haven’t quite learned that they have already become the scholars and they definitely do not trust themselves. How do we show them how to trust themselves? We ask them to explain the subject in their own words. We should listen, ask, and then listen again. They have the tools and a constructivist approach would assume that they would find their way. A consultant should say “there is the pool,” throw them, in and be the “life jacket” in case the student flounders. Nine times out of 10, the student will find their way toward a clear, scholarly, voice that belongs to them. Academic conferences in your field of study are valuable (and often initially intimidating) scholarly experiences. Since I am preparing to attend a conference next month, I’ve compiled a series of tips for applying to, getting to, and presenting at graduate and undergraduate conferences.

Academic conferences in your field of study are valuable (and often initially intimidating) scholarly experiences. Since I am preparing to attend a conference next month, I’ve compiled a series of tips for applying to, getting to, and presenting at graduate and undergraduate conferences.

Conference Etiquette

Conference Etiquette This week I am going to feature two of our amazing writing consultants and their thoughts on the best use of time and managing life during the writing process. We are losing Katy as she is moving on to a job in her field of study and expertise, but Scott will be back to discuss his ideas further in a continuing series. First up, Katy Hogue:

This week I am going to feature two of our amazing writing consultants and their thoughts on the best use of time and managing life during the writing process. We are losing Katy as she is moving on to a job in her field of study and expertise, but Scott will be back to discuss his ideas further in a continuing series. First up, Katy Hogue:

By Scott Trippel, Graduate Writing Consultant

By Scott Trippel, Graduate Writing Consultant spending 3 hours in the middle of the night, try sleeping, wake up refreshed, and get your paper done in 1 hour. I found a lot of advice about sleep hygiene online, one of the best comes from the University of Michigan Health System. You can find it here.

spending 3 hours in the middle of the night, try sleeping, wake up refreshed, and get your paper done in 1 hour. I found a lot of advice about sleep hygiene online, one of the best comes from the University of Michigan Health System. You can find it here.

A great deal of students we see at the Graduate Writing Studio are completing degrees in psychology, nursing, and physical therapy. While health-centric disciplines may not be popularly associated with writing, the GWS can offer guidance on literature reviews, case reports, evidence-based papers, and any other written projects. In a 2013 evaluation of its own writing center, the Medical University of South Carolina found “that nearly all students who used the Center agreed (and most strongly agreed) that it met their needs” and use of the Center was “associated with a better written product” (Ariail et al. 132).

A great deal of students we see at the Graduate Writing Studio are completing degrees in psychology, nursing, and physical therapy. While health-centric disciplines may not be popularly associated with writing, the GWS can offer guidance on literature reviews, case reports, evidence-based papers, and any other written projects. In a 2013 evaluation of its own writing center, the Medical University of South Carolina found “that nearly all students who used the Center agreed (and most strongly agreed) that it met their needs” and use of the Center was “associated with a better written product” (Ariail et al. 132).