Impostor syndrome, also commonly called impostor phenomenon, is the feeling that despite your many successes, you don’t deserve the recognition you are receiving. It’s most common in minority populations and those who are trying something new (read: graduate students). Students struggling with impostor syndrome feel like they don’t belong in graduate school, they link their successes with luck rather than skill, and they experience heightened anxieties about being discovered as an “impostor” by their peers. This can make students less likely to be open with their peers, submit their work for publication, feel ownership over their achievements, take risks, and make connections, due to the fear of being “found out.”

As we start out the semester, I find that many of the students I consult deal with impostor syndrome in one way or another. Either they don’t feel like they belong in a particular class, in graduate school, or in academia in general. Writing can be a huge block that prevents people from acquiring academic discourse and entering into the academic conversation. Even (and, in my experience, most often) the brightest students struggle with articulating an idea in a coherent way. This barrier can increase feelings of being an impostor, causing frustration (why can’t I just do this), self-doubt (I don’t deserve to be here), procrastination (I’d rather not do this at all than try and fail), and anxiety about writing in front of a consultant (I don’t want to bring my work in to him/her, because then he/she will know that I don’t deserve to be here). Overcoming this in a 50-minute appointment is no easy feat, but it is necessary in order to be able to help the student.

I’ve found that establishing rapport, and creating a safe atmosphere early on, to be an important first step. Demonstrating vulnerability to a student who you feel exhibits signs of impostor syndrome gives the student the freedom to be vulnerable and open as well. This safe, personal connection can help bridge the divide, and encourages students to share their writing at any stage in the process.

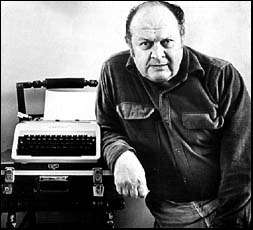

Beyond simply being friendly and open, breaking down the misconception that good writing comes naturally is another way to address impostor syndrome. Reinforcing the idea that everyone in academia must revise extensively (barring a few annoyingly talented writers, but even they have had years of practice) levels the playing field. This strategy, commonly used in writing classrooms, comes from Anne Lamott’s Shitty First Drafts. Lamott argues that the best strategy to overcome writer’s block is to write with abandon. Maybe don’t “write drunk, edit sober,” as the advice commonly misattributed to Ernest Hemingway suggests, but certainly don’t be afraid to write ugly. Encourage students to write that long, clunky sentence, and then help them edit for clarity. Emphasizing the idea that writing is a process, which relies heavily on revision, takes the pressure off those first attempts at articulating an idea, and gives hope to students who feel like “bad writers.”

A revision activity that I like is to break up a paragraph line by line, so that each sentence is its own line. The visual space between each sentence makes it easier to revise, without the clutter of the overall paragraph. Have a conversation with the student about what each sentence is saying (summarize the ideas) and what it is doing (introduction, defining, transitioning, etc.). This helps to visualize the structure of the paragraph, and the student can move the sentences around to restructure the paragraph into a logical order. After that, the student can add transition phrases, introductions, and conclusions as needed, and can ensure that the sentence structures are varied. This can help students practice revision skills, build confidence, and break through writer’s block.

Revision Activity Example

Free Write:

Writing is a process which requires reading, critical thinking, writing, and revision. Nobody writes perfectly without revision. Every good writer must revise their work. Even the ugliest, longest, most redundant sentence can be revised to be clear, concise, and to the point. Sometimes students feel embarrassed to write this way in front of consultants, because they don’t feel like they belong in graduate school, or don’t feel comfortable making a mistake in front of their consultant. Consultants should emphasize revision to make students feel more comfortable about making mistakes, and to help them feel like they belong in graduate school and will be successful.

Step One: Saying & Doing

1. Writing is a process which requires reading, critical thinking, writing, and revision.

–defines writing process

2. Nobody writes perfectly without revision.

-furthers argument

3. Every good writer must revise their work.

-furthers argument

4. Even the ugliest, longest, most redundant sentence can be revised to be clear, concise, and to the point.

–furthers argument

5. Sometimes students feel embarrassed to write this way in front of consultants, because they don’t feel like they belong in graduate school, or don’t feel comfortable making a mistake in front of their consultant.

–a reason why students struggle with this

6. Consultants should emphasize revision to make students feel more comfortable about making mistakes, and to help them feel like they belong in graduate school and will be successful.

–the reason this activity will help

Step Two: Restructure

5. Sometimes students feel embarrassed to write this way in front of consultants, because they don’t feel like they belong in graduate school, or don’t feel comfortable making a mistake in front of their consultant.

6. Consultants should emphasize revision to make students feel more comfortable about making mistakes, and to help them feel like they belong in graduate school and will be successful.

1. Writing is a process which requires reading, critical thinking, writing, and revision.

2. Nobody writes perfectly without revision.

3. Every good writer must revise their work.

4. Even the ugliest, longest, most redundant sentence can be revised to be clear, concise, and to the point.

Step Three: Revise

5. Many graduate students feel like they don’t belong in graduate school, a phenomenon called impostor syndrome. This can contribute to a student’s fear of making a mistake in front of their consultant, a common problem early on in the semester.

6. & 1. To make students more comfortable with making mistakes, and to help them feel like they belong in graduate school with their peers, consultants should emphasize writing as a process which involves reading, critical thinking, writing, and revision.

2. & 3. Nobody writes perfectly without revision, and even the best writers must revise their work.

4. With revision, even the most redundant sentence can be revised to be to the point. Creating a welcoming environment which applauds risk-taking and mistakes helps students feel at home in graduate school, and will help them overcome writer’s block in a consultation.

Result: Polished Writing

Many graduate students feel like they don’t belong in graduate school, a phenomenon called impostor syndrome. This can contribute to a student’s fear of making a mistake in front of their consultant, a common problem early on in the semester. To make students more comfortable with making mistakes, and to help them feel like they belong in graduate school with their peers, consultants should emphasize writing as a process which involves reading, critical thinking, writing, and revision. Nobody writes perfectly without revision, and even the best writers must revise their work. With revision, even the most redundant sentence can be revised to be to the point. Creating a welcoming environment which applauds risk-taking and mistakes helps students feel at home in graduate school, and will help them overcome writer’s block in a consultation.

Impostor syndrome can be a huge barrier to success in higher education. A student who doesn’t feel like they belong will be less likely to be open with their peers, make connections, submit their work for publication, or take risks, all of which are important aspects of succeeding in graduate school. Fortunately, consultants have the power to bridge that gap by providing tools for students to acquire academic discourse, enter the academic conversation, and feel like they have an ally and friend on campus who they can come to for help without judgement. This is just one example of using revision to overcome an obstacle. What are your favorite revision strategies? Have you encountered examples of impostor syndrome in your consultations? How did you work to help the student overcome it?

By: Tricia Savelli

Further Reading:

http://wrd.as.uky.edu/sites/default/files/1-Shitty%20First%20Drafts.pdf

http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2013/11/fraud.aspx

https://www.nytimes.com/2015/10/26/your-money/learning-to-deal-with-the-impostor-syndrome.html?_r=0

draft. In Anne Lamott’s edifying essay Shitty First Drafts, she claims that “the first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later” (22). I wholeheartedly agree; but how do we get to that place of play or freedom? The answer is not magical; there is no easy way to turn on the stream-of-consciousness-Kerouac-switch in our brains. The answer comes in the form of rigor, hard work, an unrelenting schedule, and draft after draft after draft until we have something that can be let loose into the intimidating world of scholarly works.

draft. In Anne Lamott’s edifying essay Shitty First Drafts, she claims that “the first draft is the child’s draft, where you let it all pour out and let it romp all over the place, knowing that no one is going to see it and that you can shape it later” (22). I wholeheartedly agree; but how do we get to that place of play or freedom? The answer is not magical; there is no easy way to turn on the stream-of-consciousness-Kerouac-switch in our brains. The answer comes in the form of rigor, hard work, an unrelenting schedule, and draft after draft after draft until we have something that can be let loose into the intimidating world of scholarly works. disappointing truth about the illusion of inspiration, he is also letting us know that, if we spend our time waiting, nothing will get done. With that being said, a poet should begin writing whether or not there is something to write about. A student/essayist, similarly, should be taking notes while reading source material. These actions motivate the writer to begin thinking about the content of their first draft in a way that is almost subconscious. But, thinking about adding one’s poems to the world of the great poets or contemplating that jump into the bigger academic conversation can be intimidating.

disappointing truth about the illusion of inspiration, he is also letting us know that, if we spend our time waiting, nothing will get done. With that being said, a poet should begin writing whether or not there is something to write about. A student/essayist, similarly, should be taking notes while reading source material. These actions motivate the writer to begin thinking about the content of their first draft in a way that is almost subconscious. But, thinking about adding one’s poems to the world of the great poets or contemplating that jump into the bigger academic conversation can be intimidating. any writer of any genre. First know your stuff and then, as Hugo would say, “get to work” (17).

any writer of any genre. First know your stuff and then, as Hugo would say, “get to work” (17).

We all know the feeling of coming back to another semester of grad school. Intense lectures and seminars, long hours of studying and preparing for exams, meeting after meeting with professors and advisors, and of course hours upon hours of writing. Simply put, life as a graduate student can be extremely demanding and at times, very overwhelming. For the most part, no matter the program you may find yourself in, the truth is you will be required to do lots of writing and eventually write a thesis, dissertation, or project. As a second year graduate student, I would like to share several tips on how to start the semester off strong, successfully make it to finals week, and eventually graduation.

We all know the feeling of coming back to another semester of grad school. Intense lectures and seminars, long hours of studying and preparing for exams, meeting after meeting with professors and advisors, and of course hours upon hours of writing. Simply put, life as a graduate student can be extremely demanding and at times, very overwhelming. For the most part, no matter the program you may find yourself in, the truth is you will be required to do lots of writing and eventually write a thesis, dissertation, or project. As a second year graduate student, I would like to share several tips on how to start the semester off strong, successfully make it to finals week, and eventually graduation.

Giving yourself time to refresh is crucial to your success. It serves as a way to reward yourself for your hard work during the week, and motivate as well, by giving you something to look forward to.

Giving yourself time to refresh is crucial to your success. It serves as a way to reward yourself for your hard work during the week, and motivate as well, by giving you something to look forward to.

It is important to educate our students on how to identify plagiarism, how to avoid it, and how to cite correctly. In fact, our librarians at California State University Fresno’s Henry Madden Library, offer workshops on “Avoiding Plagiarism” and our Grammar for Grad Students Series has also included a session on plagiarism.

It is important to educate our students on how to identify plagiarism, how to avoid it, and how to cite correctly. In fact, our librarians at California State University Fresno’s Henry Madden Library, offer workshops on “Avoiding Plagiarism” and our Grammar for Grad Students Series has also included a session on plagiarism. the ideas embodied in the research and know how to cite appropriately. This requires much more than substituting a word here and there or re-ordering a sentence. If a student has taken the time to research and understand the topic, they will be able to communicate the issues embodied in the topic in their own words.

the ideas embodied in the research and know how to cite appropriately. This requires much more than substituting a word here and there or re-ordering a sentence. If a student has taken the time to research and understand the topic, they will be able to communicate the issues embodied in the topic in their own words.

searching their biological instincts to find a way to survive the experience. They also trust that, if they fail, they will be saved. Throw the student in, but be there to save them from drowning. Grammar, logical continuity, syntax, research, outlining, the drafting process, and other processes have been a part of every graduate student’s life at some point—this is their pool of water. They may not have the vocabulary to explain these things and they may not know how to explain the functions of language on the page—they may not know that they already know how to swim—but they have been exposed enough to paddle their way to safety.

searching their biological instincts to find a way to survive the experience. They also trust that, if they fail, they will be saved. Throw the student in, but be there to save them from drowning. Grammar, logical continuity, syntax, research, outlining, the drafting process, and other processes have been a part of every graduate student’s life at some point—this is their pool of water. They may not have the vocabulary to explain these things and they may not know how to explain the functions of language on the page—they may not know that they already know how to swim—but they have been exposed enough to paddle their way to safety. Students often get caught up in sounding scholarly. When encountering this, try to ask them, “How would you write this sentence?” Often, after they have let go of that Jiminy Cricket on their shoulder who is telling them that they need to write to a scholarly audience, they dismantle the facade and rewrite the sentence in their own authoritative voice. These students haven’t quite learned that they have already become the scholars and they definitely do not trust themselves. How do we show them how to trust themselves? We ask them to explain the subject in their own words. We should listen, ask, and then listen again. They have the tools and a constructivist approach would assume that they would find their way. A consultant should say “there is the pool,” throw them, in and be the “life jacket” in case the student flounders. Nine times out of 10, the student will find their way toward a clear, scholarly, voice that belongs to them.

Students often get caught up in sounding scholarly. When encountering this, try to ask them, “How would you write this sentence?” Often, after they have let go of that Jiminy Cricket on their shoulder who is telling them that they need to write to a scholarly audience, they dismantle the facade and rewrite the sentence in their own authoritative voice. These students haven’t quite learned that they have already become the scholars and they definitely do not trust themselves. How do we show them how to trust themselves? We ask them to explain the subject in their own words. We should listen, ask, and then listen again. They have the tools and a constructivist approach would assume that they would find their way. A consultant should say “there is the pool,” throw them, in and be the “life jacket” in case the student flounders. Nine times out of 10, the student will find their way toward a clear, scholarly, voice that belongs to them. Academic conferences in your field of study are valuable (and often initially intimidating) scholarly experiences. Since I am preparing to attend a conference next month, I’ve compiled a series of tips for applying to, getting to, and presenting at graduate and undergraduate conferences.

Academic conferences in your field of study are valuable (and often initially intimidating) scholarly experiences. Since I am preparing to attend a conference next month, I’ve compiled a series of tips for applying to, getting to, and presenting at graduate and undergraduate conferences.

Conference Etiquette

Conference Etiquette This week I am going to feature two of our amazing writing consultants and their thoughts on the best use of time and managing life during the writing process. We are losing Katy as she is moving on to a job in her field of study and expertise, but Scott will be back to discuss his ideas further in a continuing series. First up, Katy Hogue:

This week I am going to feature two of our amazing writing consultants and their thoughts on the best use of time and managing life during the writing process. We are losing Katy as she is moving on to a job in her field of study and expertise, but Scott will be back to discuss his ideas further in a continuing series. First up, Katy Hogue:

By Scott Trippel, Graduate Writing Consultant

By Scott Trippel, Graduate Writing Consultant spending 3 hours in the middle of the night, try sleeping, wake up refreshed, and get your paper done in 1 hour. I found a lot of advice about sleep hygiene online, one of the best comes from the University of Michigan Health System. You can find it here.

spending 3 hours in the middle of the night, try sleeping, wake up refreshed, and get your paper done in 1 hour. I found a lot of advice about sleep hygiene online, one of the best comes from the University of Michigan Health System. You can find it here.

A great deal of students we see at the Graduate Writing Studio are completing degrees in psychology, nursing, and physical therapy. While health-centric disciplines may not be popularly associated with writing, the GWS can offer guidance on literature reviews, case reports, evidence-based papers, and any other written projects. In a 2013 evaluation of its own writing center, the Medical University of South Carolina found “that nearly all students who used the Center agreed (and most strongly agreed) that it met their needs” and use of the Center was “associated with a better written product” (Ariail et al. 132).

A great deal of students we see at the Graduate Writing Studio are completing degrees in psychology, nursing, and physical therapy. While health-centric disciplines may not be popularly associated with writing, the GWS can offer guidance on literature reviews, case reports, evidence-based papers, and any other written projects. In a 2013 evaluation of its own writing center, the Medical University of South Carolina found “that nearly all students who used the Center agreed (and most strongly agreed) that it met their needs” and use of the Center was “associated with a better written product” (Ariail et al. 132). The quiet is deafening. Students have gone home for the holiday break and the Graduate Writing Studio is, for the most part, empty. It is a time for reflection and looking toward next semester. Here are some things to look forward to:

The quiet is deafening. Students have gone home for the holiday break and the Graduate Writing Studio is, for the most part, empty. It is a time for reflection and looking toward next semester. Here are some things to look forward to: